The Times found much to write about.

I did not. Street demonstrations continue.

http://earlywarn.blogspot.com/2012/09/piigs-unemployment.html

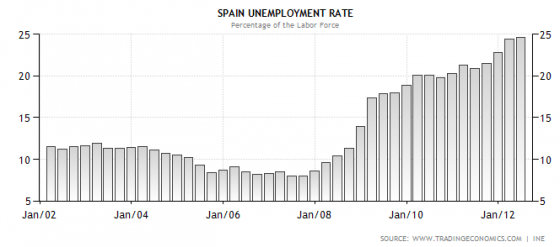

PIIGS Unemployment

The data run through July except for Greece where they only go through June.

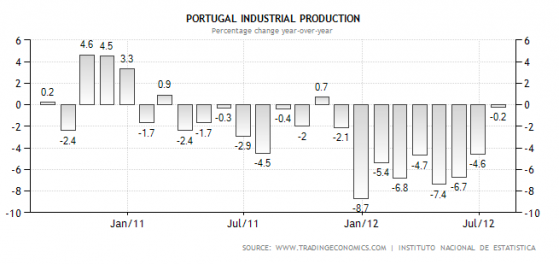

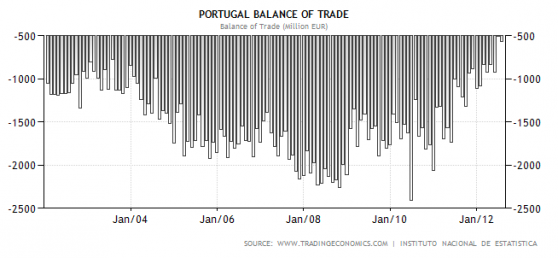

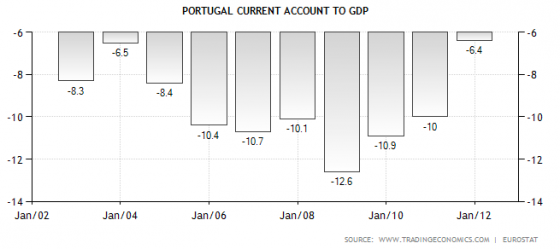

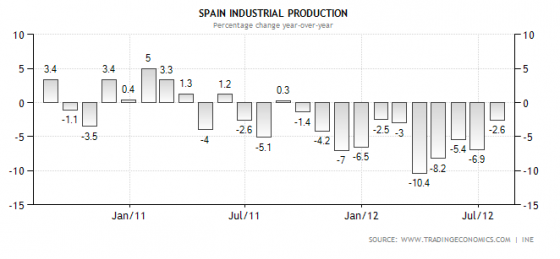

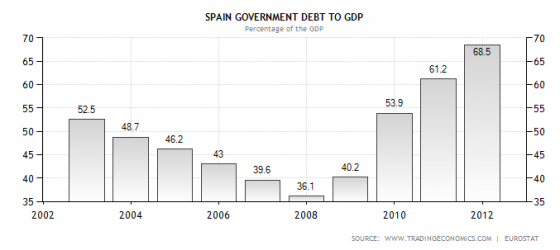

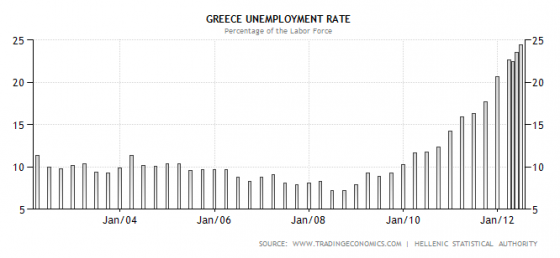

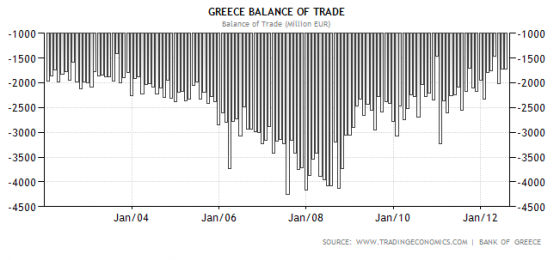

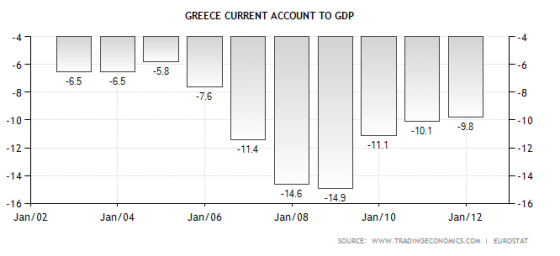

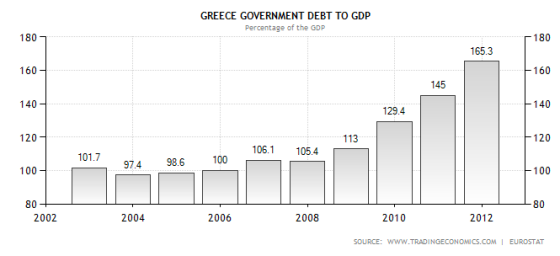

Spain and Greece have continued to worsen, while nowhere on the periphery is improving yet. There are very serious protests in at least Spain, Greece, and Portugal. The European crisis remains very much unsolved.

Krugman is distracted:

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/09/29/short-political-memories/

Short Political Memories

Busy

day, so not much time for posting. Just a note about the oddly short

memories of many people commenting on this final stretch of the

presidential campaign.

First, there’s the agonizing of Republicans over the choice of Mitt Romney as the party’s paladin. As Jonathan Chait points out, you really have to remember primary season (which shouldn’t be hard, given that it was just the other day, but seems to have vanished into the mists). The fact was that all the non-Mitts were awesomely terrible, indeed ludicrous. The only contender who even looked on paper like a real alternative, Rick Perry, turned out to have three major liabilities: he was inarticulate, he was slow on his feet, and I can’t remember the third (sorry, couldn’t help myself).

Second, people wondering why Paul Ryan hasn’t been able to sell his message; these people have forgotten how the Ryan phenomenon ever happened. Ryan was never able to sell his message to the general public. His constituency was always the Beltway establishment, which had decided that he was the Brave Truth-teller. There was never any good reason to believe that voucherizing Medicare would be anything but desperately unpopular.

Third — and this is prospective — people now invoking the 2004 debates as an example of game-changers (Kerry cut dramatically into a big Bush lead) are, I suspect, failing to remember what happened in that first debate, which was that Bush came across as a total idiot. I suppose this could happen to Obama, but it would certainly be out of character.

So my take is that the GOP was fated to have a weak candidate; that it was predictable that Ryan would be a liability, not an asset; and that anyone imagining that Romney can turn this around on Wednesday is hoping for a very unlikely event."

First, there’s the agonizing of Republicans over the choice of Mitt Romney as the party’s paladin. As Jonathan Chait points out, you really have to remember primary season (which shouldn’t be hard, given that it was just the other day, but seems to have vanished into the mists). The fact was that all the non-Mitts were awesomely terrible, indeed ludicrous. The only contender who even looked on paper like a real alternative, Rick Perry, turned out to have three major liabilities: he was inarticulate, he was slow on his feet, and I can’t remember the third (sorry, couldn’t help myself).

Second, people wondering why Paul Ryan hasn’t been able to sell his message; these people have forgotten how the Ryan phenomenon ever happened. Ryan was never able to sell his message to the general public. His constituency was always the Beltway establishment, which had decided that he was the Brave Truth-teller. There was never any good reason to believe that voucherizing Medicare would be anything but desperately unpopular.

Third — and this is prospective — people now invoking the 2004 debates as an example of game-changers (Kerry cut dramatically into a big Bush lead) are, I suspect, failing to remember what happened in that first debate, which was that Bush came across as a total idiot. I suppose this could happen to Obama, but it would certainly be out of character.

So my take is that the GOP was fated to have a weak candidate; that it was predictable that Ryan would be a liability, not an asset; and that anyone imagining that Romney can turn this around on Wednesday is hoping for a very unlikely event."

Saturday, September 29, 2012

Links 09/29/2012

A River Runs Through…Gale Crater Scientific American

Dioxin Causes Disease and Reproductive Problems Across Generations, Study Finds Science Daily (CL)

Energy wonder crop Arundo raises invasive fears Raleigh News & Observer

Mathematics at Google [PDF]. Interesting!

Faltering Chinese Demand Affecting a Broad Range of Industries Financial Armageddon

China’s Bo Xilai expelled and faces criminal charges BBC

Bo Xilai expelled from CPC, public office Xinhua. Official prose, Chinese style.

Bo Xilai Falls, China’s Microbloggers Gloat WSJ

The Bo Xilai Case: China’s Pandora’s Box New Yorker

A tail-risk short position that will pay off soon John Dizard, FT

Dad, you were right Gillian Tett, FT. A penny for the old guy?

Spanish banks need over 50 billion euros to clean up balance sheets EL Pais (report).

Catalan parliament approves resolution on self-determination El Pais

Portugal at flashpoint as austerity lights fires in mild-mannered populace Guardian

Austerity hurts blood donations Ekathimerini

French budget raises taxes on rich Al Jazeera

What the Pope’s butler saw Independent. Power struggles in the Vatican.

Libya thwarts planned anti-militia protests Reuters. No Second Amendment in Libya?

Intelligence officials explain ‘evolving’ US understanding of attack on consulate in Libya AP

Intelligence office says it got Libya attack wrong, not White House McClatchy. Falling on their sword?

Obama blocks Chinese purchase of US wind farms AP. They’re near a drone base.

Fed’s Fisher says U.S. “drowning in unemployment” Reuters

BofA pays $2.4 billion to settle claims over Merrill Reuters

Foreclosure Fraud Settlement Update: Checks to Victims, Servicing Standards, Ongoing Lawsuits David Dayen, FDL

The secrets of Buffett’s success Economist

Horatio Alger, RIP National Journal

Does economic growth make you happy? TLS

The politics of central banking Dan Hind, Al Jazeera

Union Man The New Yorker. William Seward.

Want to Build Resilience? Kill the Complexity HBR

Dioxin Causes Disease and Reproductive Problems Across Generations, Study Finds Science Daily (CL)

Energy wonder crop Arundo raises invasive fears Raleigh News & Observer

Mathematics at Google [PDF]. Interesting!

Faltering Chinese Demand Affecting a Broad Range of Industries Financial Armageddon

China’s Bo Xilai expelled and faces criminal charges BBC

Bo Xilai expelled from CPC, public office Xinhua. Official prose, Chinese style.

Bo Xilai Falls, China’s Microbloggers Gloat WSJ

The Bo Xilai Case: China’s Pandora’s Box New Yorker

A tail-risk short position that will pay off soon John Dizard, FT

Dad, you were right Gillian Tett, FT. A penny for the old guy?

Spanish banks need over 50 billion euros to clean up balance sheets EL Pais (report).

Catalan parliament approves resolution on self-determination El Pais

Portugal at flashpoint as austerity lights fires in mild-mannered populace Guardian

Austerity hurts blood donations Ekathimerini

French budget raises taxes on rich Al Jazeera

What the Pope’s butler saw Independent. Power struggles in the Vatican.

Libya thwarts planned anti-militia protests Reuters. No Second Amendment in Libya?

Intelligence officials explain ‘evolving’ US understanding of attack on consulate in Libya AP

Intelligence office says it got Libya attack wrong, not White House McClatchy. Falling on their sword?

Obama blocks Chinese purchase of US wind farms AP. They’re near a drone base.

Fed’s Fisher says U.S. “drowning in unemployment” Reuters

BofA pays $2.4 billion to settle claims over Merrill Reuters

Foreclosure Fraud Settlement Update: Checks to Victims, Servicing Standards, Ongoing Lawsuits David Dayen, FDL

The plan is to pay out the claims in mid-2013. If this works and they get the target of 750,000 responses, then the payout will amount to $2,000 “sorry your home was stolen” checks. However, the challenge will come in actually finding these homeowners, who after all lost their home and experienced an upheaval in their lives. They may have left a forwarding address, and presumably that’s where these claim forms are being sent, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that the families still live there. Moreover, foreclosure victims may be wary of anything through the mail that has their old bank’s name on it and references their past foreclosure. Hopefully the packet doesn’t look like the bank going after them for a deficiency judgment.Transactional Attorney Ethics Adam Levitin, Credit Slips

The secrets of Buffett’s success Economist

Horatio Alger, RIP National Journal

Does economic growth make you happy? TLS

The politics of central banking Dan Hind, Al Jazeera

Union Man The New Yorker. William Seward.

Want to Build Resilience? Kill the Complexity HBR

Ireland risks becoming 'feeder nation’

Ireland is destined to become a “feeder nation” reliant on money being sent home from workers abroad, a leading hedge fund has warned, dashing hopes of a return to the “Celtic Tiger”.

29 Sep 2012

| 10 Comments

Thousands of Portuguese protest against cuts

Thousands of Portuguese protested on Saturday against austerity, stepping up their opposition to the country's €78bn bailout ahead of new spending cuts and tax hikes to be announced in the government's 2013 draft budget.

29 Sep 2012

| Comment

Spain debt rises on aid to banks and regions

Spain's debt level and borrowing needs are set to rise next year, piling pressure on the government to apply for international aid, as it pours funds in to cash-strapped regions and an ailing banking system, its budget showed on Saturday.

29 Sep 2012

| Comment-

30 Sep 2012: John Carlin: The country needs more than a bailout. It needs a revolutionary change in its hidebound social structures

-

30 Sep 2012: The single currency continues to be rocked by market turmoil, and there are five good reasons why things could get much worse before they get any better, writes Heather Stewart

-

-

28 Sep 2012: Ha-Joon Chang: No wonder the protesters are back. They are angry at the backdoor rewriting of the social contract

-

28 Sep 2012: Editorial: François Hollande's budget – the toughest in 30 years – is ameliorative but it is hardly a radical departure.

-

-

28 Sep 2012: With half a million homes without a breadwinner and grandparents being pulled out of care homes for their pensions, separatist sentiments are brewing in a country that can take no more strain

I have a number of printers I have not bothered to use.

Hard copy is mostly for the files. The cloud is doing well as a file.

You are just going to have to tell me what you want me to know.

You have a concealed carry license from Massachusetts.

Wen Hair Products have drawn several bad reviews.

I see little that is complimentary.

I can and will find the studs. Hanging pictures is not that much of a deal.

AT&T smart phone add addressed to me. Others may be a better deal.

I would have to study the contract.

The more I learn about the smart phone business the less happy it makes me.

Auto insurance is very competitive. Talk to an agent.

I expect there are no real bargains.

.

140 Comments

140 Comments