444444444444444444444

-

Luckycharms

-

Does IMF Stand for Impressive Macroeconomic Flexibility?

So the IMF is holding a meeting on rethinking macroeconomic policy (I was invited but couldn’t make the timing work.) And the Fund’s chief economist has already made it clear that he’s open to some serious revision of the prevailing paradigm.

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2012/01/satyajit-das-europe%E2%80%99s-the-road-to-nowhere-part-ii-%E2%80%93-roadblocks-ahead.html

Op-Ed Columnist

Is Our Economy Healing?

By PAUL KRUGMAN

Published: January 22, 2012

How goes the state of the union? Well, the state of the economy remains terrible. Three years after President Obama’s inauguration and two and a half years since the official end of the recession, unemployment remains painfully high.

But there are reasons to think that we’re finally on the (slow) road to better times. And we wouldn’t be on that road if Mr. Obama had given in to Republican demands that he slash spending, or the Federal Reserve had given in to Republican demands that it tighten money.

Why am I letting a bit of optimism break through the clouds? Recent economic data have been a bit better, but we’ve already had several false dawns on that front. More important, there’s evidence that the two great problems at the root of our slump — the housing bust and excessive private debt — are finally easing.

On housing: as everyone now knows (but oh, the abuse heaped on anyone pointing it out while it was happening!), we had a monstrous housing bubble between 2000 and 2006. Home prices soared, and there was clearly a lot of overbuilding. When the bubble burst, construction — which had been the economy’s main driver during the alleged “Bush boom” — plunged.

But the bubble began deflating almost six years ago; house prices are back to 2003 levels. And after a protracted slump in housing starts, America now looks seriously underprovided with houses, at least by historical standards.

So why aren’t people going out and buying? Because the depressed state of the economy leaves many people who would normally be buying homes either unable to afford them or too worried about job prospects to take the risk.

But the economy is depressed, in large part, because of the housing bust, which immediately suggests the possibility of a virtuous circle: an improving economy leads to a surge in home purchases, which leads to more construction, which strengthens the economy further, and so on. And if you squint hard at recent data, it looks as if something like that may be starting: home sales are up, unemployment claims are down, and builders’ confidence is rising.

Furthermore, the chances for a virtuous circle have been rising, because we’ve made significant progress on the debt front.

That’s not what you hear in public debate, of course, where all the focus is on rising government debt. But anyone who has looked seriously at how we got into this slump knows that private debt, especially household debt, was the real culprit: it was the explosion of household debt during the Bush years that set the stage for the crisis. And the good news is that this private debt has declined in dollar terms, and declined substantially as a percentage of G.D.P., since the end of 2008.

There are, of course, still big risks — above all, the risk that trouble in Europe could derail our own incipient recovery. And thereby hangs a tale — a tale told by a recent report from the McKinsey Global Institute.

The report tracks progress on “deleveraging,” the process of bringing down excessive debt levels. It documents substantial progress in the United States, which it contrasts with failure to make progress in Europe. And while the report doesn’t say this explicitly, it’s pretty clear why Europe is doing worse than we are: it’s because European policy makers have been afraid of the wrong things.

In particular, the European Central Bank has been worrying about inflation — even raising interest rates during 2011, only to reverse course later in the year — rather than worrying about how to sustain economic recovery. And fiscal austerity, which is supposed to limit the increase in government debt, has depressed the economy, making it impossible to achieve urgently needed reductions in private debt. The end result is that for all their moralizing about the evils of borrowing, the Europeans aren’t making any progress against excessive debt — whereas we are.

Back to the U.S. situation: my guarded optimism should not be taken as a statement that all is well. We have already suffered enormous, unnecessary damage because of an inadequate response to the slump. We have failed to provide significant mortgage relief, which could have moved us much more quickly to lower debt. And even if my hoped-for virtuous circle is getting under way, it will be years before we get to anything resembling full employment.

But things could have been worse; they would have been worse if we had followed the policies demanded by Mr. Obama’s opponents. For as I said at the beginning, Republicans have been demanding that the Fed stop trying to bring down interest rates and that federal spending be slashed immediately — which amounts to demanding that we emulate Europe’s failure.

And if this year’s election brings the wrong ideology to power, America’s nascent recovery might well be snuffed out.

More Krugman:

"April 1, 2011, 5:25 pm1921 and All That

Every once in a while I get comments and correspondence indicating that the right has found an unlikely economic hero: Warren Harding. The recovery from the 1920-21 recession supposedly demonstrates that deflation and hands-off monetary policy is the way to go.

But have the people making these arguments really looked at what happened back then? Or are they relying on vague impressions about a distant episode, with bad data, that has been spun as a confirmation of their beliefs?

OK, I’m not going to invest a lot in this. But even a cursory examination of the available data suggests that 1921 has few useful lessons for the kind of slump we’re facing now.

Brad DeLong has recently written up a clearer version of a story I’ve been telling for a while (actually since before the 2008 crisis) — namely, that there’s a big difference between inflation-fighting recessions, in which the Fed squeezes to bring inflation down, then relaxes — and recessions brought on by overstretch in debt and investment. The former tend to be V-shaped, with a rapid recovery once the Fed relents; the latter tend to be slow, because it’s much harder to push private spending higher than to stop holding it down.

And the 1920-21 recession was basically an inflation-fighting recession — although the Fed was trying to bring the level of prices, rather than the rate of change, down. What you had was a postwar bulge in prices, which was then reversed:

Money was tightened, then loosened again:

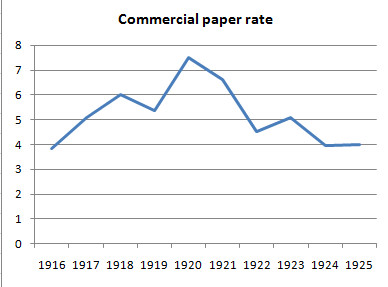

Discount rates are a problematic indicator, but here’s what happened to commercial paper rates:

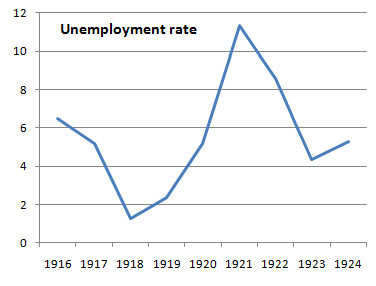

And so there was a V-shaped recovery: Historical statistics, Millennial edition

Historical statistics, Millennial edition

The deflation may have helped by increasing the real money supply — at least Meltzer thinks so (pdf) — but if so, the key point was that the economy was nowhere near the zero lower bound, so there was plenty of room for the conventional monetary channel to work.

All of this has zero relevance to an economy in our current situation, in which the recession was brought on by private overstretch, not tight money, and in which the zero lower bound is all too binding.

So do we have anything to learn from the macroeconomics of Warren Harding? No."

-

-

The iPhone Economy

Paul Krugman:

Apple And Agglomeration

The big Times article on Apple manufacturing was excellent, and I’ll have more to say about it when I have the time. One thing worth noting right away, however, is that the piece is in large part an essay on the economies of agglomeration (pdf, wonkish):

“The entire supply chain is in China now,” said another former high-ranking Apple executive. “You need a thousand rubber gaskets? That’s the factory next door. You need a million screws? That factory is a block away. You need that screw made a little bit different? It will take three hours.”

The point is that manufacturing plants don’t exist in isolation; they benefit a lot from being part of a manufacturing cluster, with specialized suppliers and a large pool of workers with the right skills close at hand. This is the kind of stuff I emphasized in my own work on both trade and economic geography.

The policy implications aren’t as clear as you might imagine. But more about that when I have time to do it right."

The link is:

www.princeton.edu...7Epkrugman/deardorff.pdf

.

No comments:

Post a Comment